“New Religious Movement” is one of those tricky, catch-all terms that can refer to lots of different communities, including ones that have very little in common.

Broadly, a New Religions Movement (NRM) is a religious group that came into existence more recently (typically somewhere around the 19th century or later). Other terms include alternative spiritualities, alternative religions or simply “new religions.” Usually NRMs are considered on the fringes in some way; the term often used for groups that are considered outside of the mainstream, and are frequently talked about in the same context as “cults.”

This is where things get really dicey. Because when we hear the term “cult,” we already think we know everything there is to know about that group. They’re dangerous. They’re deviant. They don’t deserve to be called a “real” religion. As Northeastern University professor Megan Goodwin pointed out, using “cult” to label religious or social groups that we don’t like or that we consider “strange” often marks those communities as “legitimate targets of state surveillance and violence.”

Groups that have been referred to as “cults” include the Aum Shinrikyo, the Black Hebrew Israelites, the Branch Davidians, the Church of Scientology, Heaven’s Gate, the Manson Family, the Peoples Temple, Raëlism, and QAnon.

Part of the reason some people use the label is because some of the groups that fall into this category are known for saying and doing things that are problematic, or abusive. So why is it inappropriate to use the word? For one thing, virtually no one who is part of a group labeled as a “cult” sees themself as a cult member. Rather they are a believer, disciple, or part of a religious community. Perhaps even more troubling is the power of the word “cult” and the public probing or state-sanctioned opprobrium it can bring. Once the label is applied – and despite changing ideas about what is and what isn’t a cult – it is virtually impossible to shake the association, and it can have extraordinary life or death consequences.

It is common for family members, ex-members, law enforcement and media to use the term “cult” to drum up interest about, discredit or accuse these groups. The label comes with certain stereotypes: a charismatic leader, dangerous rituals, “end times” prophecies or other seemingly strange and reclusive behaviors that don’t fit our definition of what a “real religion” should be.

This Reporting Guide explores reporting, analysis and commentary on NRMs, helping you better understand the communities the term describes and report thoughtfully, carefully and sensitively on the subject.

Table of Contents:

- Background and Terminology

- Terms and Definitions

- Reporter Tips and Red Flags

- A Brief Introduction to Several NRMs

- Sources and Experts

- Related ReligionLink Content

Background and Terminology

In general, whenever a news story about such a community comes to the fore, readers tend to get freaked out and fascinated all at the same time. That heady mix seems to sell.

Despite some skepticism about the term and its use, moviemakers, columnists, podcasters and journalists continue to cash in on the allure of “cult” stories. Search any streaming platform and you’ll quickly find a selection of documentaries — like 2017’s Wild Wild Country, about Indian guru Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh and his onetime community of followers in Wasco County, Oregon. Even popular action-adventure games like “Cult of the Lamb” play on popular ideas and images around cults and their dark, alluring secrecy and power.

If popular culture were not powerful enough to push the “cult” narrative, questions about a supposed cult member’s involvement in the assassination of former Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and the anniversaries of horrendous and infamous events such as Jonestown, Waco and Heaven’s Gate keep the dangers of “cults” at the forefront of our minds year after year.

Even so, most (though not all) religion journalists and scholars agree: The word “cult” should be shelved.

In popular parlance, the word “cult” is used to mark certain social groups as irregular, predatory, abusive, irrational, dangerous, and outside the bounds of what we consider “real” religion. These groups are often led by a charismatic personality, may have an “end times” (or apocalyptic/millennial) orientation, and often live within a highly controlled environment or stringently codified moral system.

Some organizations say there are specific criteria that make a group a cult, and sometimes it is helpful to use the term if it fits. According to these characteristics, Jonestown, as Ori Tavor put it, could be considered the “quintessential cult.” It featured a charismatic leader in Jim Jones, who fit what James T. Richardson called the, “myth of the omnipotent leader” and the tragic deaths of 918 followers by poison matched the, “myth of the passive, brainwashed follower.”

Although the term “cult” may seem an apt descriptor for some communities, a scholar who studies New Religious Movements (particularly the Branch Davidians), Catherine Wessinger, calls into question the process by which some communities get called a “cult” and how others don’t. Wessinger calls this process, “culting:”

once the label ‘cult’ has been applied it tends to stick, and it can inhibit careful investigation of what is going on inside a religious group and its interactions with members of society; broadly speaking, it is assumed that people ‘know’ what goes on in a ‘cult.’

This kind of discourse is not only detrimental to the group in question, but dehumanizes its members. This can even lead to direct harm to the very people we claim we want to protect or rescue (as in Waco, TX with the Branch Davidians or in the he Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints [FLDS Church]).

The resources below take you deeper into the debate on terminology, why it matters, and how to understand how the term NRM — or “cult” — is used to label specific movements or communities:

Books

- Read Cultish: The Language of Fanaticism, by Amanda Montell (2021)

- Read Handbook of East Asian New Religious Movements, by Lukas Pokorny, Franz Winter (2018)

- Read Handbook of Scientology, by James R. Lewis (2017)

- Read The FBI and Religion: Faith and National Security Before and After 9/11, edited by Sylvester A. Johnson and Steven Weitzman (2017)

- Read The Oxford Handbook of New Religious Movements: Volume II (2nd edn), by James R. Lewis and Inga Tøllefsen (2016)

- Read Handbook of Nordic New Religions, by James R. Lewis and Inga Bådsen Tøllefsen (2015)

- Read Bloomsbury Companion to New Religious Movements, by George D. Chryssides and Benjamin E. Zeller (2014)

- Read Controversial New Religions, by James R. Lewis and Jesper Aa. Petersen (2014)

- Read Heaven’s Gate: America’s UFO Religion, by Benjamin E. Zeller (2014)

- Read Cambridge Companion to New Religious Movements, by Olav Hammer and Mikael Rothstein (2012)

- Read New Religious Movements: A Guide for the Perplexed, by Paul Oliver (2012)

- Read Cults: A Reference and Guide, by James R. Lewis (2012)

- Read The Church of Scientology: A History of a New Religion, by Hugh B. Urban (2011)

- Read Cults, Religion, and Violence, edited by David G. Bromley and J. Gordon Melton (2002)

- Read How the Millennium Comes Violently: From Jonestown to Heaven’s Gate, by Catherine Wessinger (2000)

- Read The Making of a Moonie: Brainwashing or Choice? by Eileen Barker (1985)

Articles, Commentary and Analysis

- Read “Compared to What? ‘Cults’ and ‘New Religious Movements,’” by Eugene V. Gallagher.

- Read “Factsheet: New Religious Movements,” from the Religion Media Centre.

- Read “Unpacking the Bunker: Sex, Abuse, and Apocalypticism in ‘Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt,’” by Megan Goodwin.

- Read “Insights from a Religion Reporter,” by Kali Handelman and Sam Kestenbaum.

- Read “The Public Perception of ‘Cults’ and ‘New Religious Movements,’” by Paul J. Olson.

- Listen to “Smart Grrl Summer: What are ‘cults’? Why do we hate that word so much?” from the “Keeping it 101 Podcast.”

- Listen to “Cults and NRMs” from the Religious Studies Project.

- Read “Is it a cult, or a new religious movement?” by Tina Rodia.

- Read “Why the label ‘cult’ gets in the way of understanding new religions,” from Religion News Service.

- Listen to “New Directions in the Study of Scientology” from the Religious Studies Project.

- Read “New Books in New Religious Movements, 2015-2018” by Courtney Applewhite.

- Listen to “Millennialism and Violence?” from the Religious Studies Project.

- Listen to “Minority Religions and the Law” from the Religious Studies Project.

Reports and Other Resources

- Explore the Critical Dictionary of Apocalyptic and Millenarian Movements (CDAMM) from the Centre for the Critical Study of Apocalyptic and Millenarian Movements (CenSAMM).

- Read “New Religious Movements,” from Hartford Institute for Religion Research.

Example Coverage

Shinzo Abe’s Assassin and Japan’s Complicated Spirituality

By Hiroko Yoda, The New Yorker

July 26, 2022

(New Yorker) – The killing of the former Prime Minister of Japan, Shinzo Abe, on July 8th, sent shock waves rippling across Japan and the globe. Even after stepping down as Prime Minister, in the summer of 2020, owing to health issues, Abe was that rarest of presences on the Japanese political scene: an internationally recognizable face, even a celebrity. His hawkish brand of conservatism divided Japan and infuriated many leaders in the region, but endeared him to others, most famously Donald Trump. And, as the single longest-serving prime minister in Japan’s history, he remained, in many ways, the country’s face to the world.

The brazen daylight shooting, days before a major national election, initially seemed, to many, like a case of political violence. Prime Minister Fumio Kishida declared, “We must defend free and just elections, which are the basis of democracy,” and said that Japan would “never yield to violence.” The sentiment was echoed and amplified by other political parties, who explicitly framed the shooting as an act of “terrorism.” This narrative began to crumble when the police released a statement that the gunman, Tetsuya Yamagami, a forty-one-year-old Nara resident, professed no issues with Abe’s politics. Instead, it seemed, he had been motivated by a grudge against a religious group that he considered Abe to be associated with. Yamagami blamed the Family Federation for World Peace and Unification, otherwise known as the Unification Church, for destroying his family. His mother had donated more than a hundred million yen over the years, since joining the church, in 1998, plunging the family into dire poverty. After a series of attempts to attack church members and facilities, the alleged assassin had switched his focus to Abe.

The connections between Abe’s family and Sun Myung Moon, the Korean religious leader who founded the Unification Church, are little discussed in mainstream Japanese media but well documented. Moon created the Federation for Victory Over Communism, a political wing of the Unification Church, in 1968. During the Cold War, he used church influence to forge inroads with world leaders, including Japanese ones. Moon’s ties to the Abe family extend back three generations. The former Prime Minister Nobusuke Kishi—Abe’s grandfather—and his allies spoke highly of Moon and his adherents, and Abe’s party, the Liberal Democratic Party, often counted on volunteer labor and a bloc of votes from Moon’s followers in support of its campaigns. These included those of Abe’s father, Shintaro, who was first elected to the Diet in 1958 and who was a leading candidate to become Prime Minister in the nineteen-eighties, before a scandal derailed his ambitions. Abe’s personal connections to the Unification Church surfaced in 2006, when the press reported that he had sent a congratulatory message to the participants at a church-affiliated event being held in Fukuoka. Last September, Abe made an appearance, along with Donald Trump, at the Unification Church’s digital Rally of Hope, convened under the auspices of Moon’s widow, Hak Ja Han Moon. “The inspiration that they have caused for the entire planet is unbelievable,” Abe said of the Moon family.

The revelation of the church connection added yet another layer of strangeness to Abe’s assassination, for Japan is not widely associated with religious extremism or gun violence. The Japanese constitution, framed by American occupying forces and enacted in 1947, stipulates that “the State and its organs shall refrain from religious education or any other religious activity.” Yamagami’s makeshift weapon testifies to how difficult it is to procure a gun. But his alleged crime also sheds light on the fact that Japan isn’t nearly as secular a nation as many, including its own citizens, believe it to be.

Example Coverage

Just Say No: The Four-Letter Word Religion Writers Really Want To Avoid

By Bobby Ross Jr., Religion Unplugged

April 1, 2022

(Religion Unplugged) – “Don’t Call It a Cult.”

That was the title of one of the more intriguing sessions at last week’s Religion News Association annual meeting, held at a Washington, D.C.-area hotel.

Moderated by independent audio journalist Sarah Ventre, the panel featured Anuttama Dasa, global communications director for the International Society for Krishna Consciousness; Melissa Weisz, a podcaster who grew up in a Hasidic Jewish community; and Shirlee Draper, who was born and raised within a polygamous sect known as the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints.

“The goal was to explore the ways in which we report on marginalized religious communities, particularly those that are often referred to as ‘cults,’” said Ventre, who hosted the award-winning 2020 podcast ”Unfinished: Short Creek,” about the fundamentalist Mormon community where Draper grew up on the Utah-Arizona border.

“I wanted to unpack the responsibilities we have both to our audience and to our sources,” the moderator added, “and examine the ways in which our reporting affects the communities we report on long after we publish.”

“Show, don’t tell” is a journalistic adage.

This session reinforced the importance of describing a specific pattern of abusive or manipulative behavior rather than resorting to more generalized terms like “cult” or “brainwashed.”

That’s not to say sources can’t describe their own experience as having escaped from a cult. Nor do journalists have to be completely relativist: They have a responsibility, to the extent possible, to evaluate and assess people’s — and leaders’ — accounts. Often, groups do have systemic ways of enabling abusers and abusive behavior, and journalists can identify that where they can verify it.

But news organizations need to be careful.

Just this week, Texas Monthly published an in-depth piece on an East Texas church the magazine described as “an insular fundamentalist religious group that some consider a cult.” The reporting is strong, but I’m not certain the cult reference is necessary.

I was curious, so I checked my own archive to see when I’ve used the term “cult”: It came up in a 2018 Religion News Service story I wrote on the 25th anniversary of David Koresh and 75 Branch Davidian followers dying in a firestorm near Waco, Texas. But the mentions were in a quote and a book title.

A new entry in the Associated Press’ updated religion stylebook seems appropriate:

cult A loaded term to be used with caution.

Or even better, as a Godbeat friend put it, “a whole lot of caution.”

“The only time I use it is when quoting someone who uses it or with a caveat along the lines of, ‘a term most scholars who study religion reject for its tone of judgment,’” said Kimberly Winston, a veteran religion journalist who freelances for publications including ReligionUnplugged.com. “To me, it carries the potential to inflict pain on people within the group being called a cult, and that’s something I try my best to avoid.”

Kelsey Dallas, who covers religion for the Deseret News in Salt Lake City, agreed: “The issue with the word ‘cult’ is that it comes with a strong negative connotation. By using it, reporters risk drowning out the nuance within the stories people have to tell about their experiences in controversial faith groups. The panelists at RNA told us that they want the freedom to share good memories as well as the bad ones.”

Terms and Definitions

Anticult Movement: According to the Historical Dictionary of New Religious Movements, “a group of organizations, principally in the United States and Europe, that are actively opposed to the activities of NRMs. The term tends to be rejected by critics of NRMs on the grounds that they claim not to be against cults indiscriminately but to be against unacceptable practices of which certain NRMs are guilty. Notwithstanding such disclaimers, however, the attitude of the anticult movement (ACM) appears consistently negative toward the vast majority of new religions. The ACM is sometimes distinguished from the countercult movement, the latter being more concerned to provide written and verbal critiques of NRMs’ teachings, often from a Christian perspective.”

Apocalypticism: According to the Critical Dictionary of Apocalyptic and Millenarian Movements (CDAMM), “in popular usage, ‘apocalypticism’ refers to a belief in the likely or impending destruction of the world (or a general global catastrophe), usually associated with upheaval in the social, political, and religious order of human society—often referred to as an/the ‘apocalypse’. Historically, the term has had religious connotations and the great destruction has traditionally been seen as part of a divine scheme, though it is increasingly used in secular contexts.”

Brainwashing: Refers to a technique of manipulation and/or coercion to get believers of a group to abandon logic and follow the groupthink of their new community. The term is extremely controversial, and there is a lack of evidence indicating that “brainwashing” understood in this way is even possible. Instead of using this word, try to explain the process of what has happened to someone and the ways in which they do or don’t have agency in it (e.g., explain how someone manipulated or coerced another person rather than relying on the “brainwashing” trope).

Closed Community/Insular Community: These terms refer to communities that have limited contact with those considered “outsiders.” Be careful when using these terms (particularly “closed community”), because their use can imply stark divisions that may appear black and white, but are actually quite nuanced. Best practice would be to describe the beliefs, behaviors and practices particular to the group you are reporting on.

Compound: A pejorative term used to refer to a large, communal dwelling, often as part of an intentional community that is religiously or spiritually rooted. This term should be avoided because of its particularly negative and sinister connotations. Instead, describe the space and its characteristics.

Cult: Often used to refer to a spiritual or religious group that exists outside of the mainstream, has new or uncommon ideologies, and is considered strange, dangerous or problematic by the person using the term. When journalists use this term in their work, it legitimizes the definition and makes it much more likely that others will use it for the same group. Generally to be avoided in your reporting, along with related terms like “cultish” or “cult-like.”

Fundamentalist/fundamentalism: Broadly speaking, this term refers to people who believe in a literal interpretation of holy scripture and apply strict interpretations to the laws and practices of their faith. It is most frequently used in reference to Christianity, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and Islam, though is used for other faiths as well. The term can sometimes be used to denote extremism, non-modern thinking, irrational beliefs or has political connotations, though it is not considered pejorative by all. Fundamentalists, however, are quite conventional, modern, rational, and can be apolitical. Best practice is to ask your source if they identify as fundamentalist before you apply the term.

High Demand Religion (or High Demand Group): Often used to describe groups that require their members to participate in certain actions, routines or rituals that may be deemed controlling or manipulative. This could include groups that monitor their members communications (particularly with nonmembers), require their members to be awake for long periods of time or follow particularly restrictive diets. This term is often used as a substitute for “cult,” but many who find the word cult problematic find this term problematic as well.

Millenarianism: According to the Critical Dictionary of Apocalyptic and Millenarian Movements (CDAMM), “in popular and academic use, the term ‘millenarianism’ is often synonymous with the related terms ‘millennialism’, ‘chiliasm’ and ‘millenarism’ (Though these terms are often used synonymously, please be aware that they are different, and it’s helpful to distinguish millennialism from millenarianism, for example). They refer to an end-times Golden Age of peace, on earth, for a long period, preceding a final cataclysm and judgment—sometimes referred to as the ‘millennium’. The terms are used to describe both millenarian belief and the persons or social groups for whom that belief is central.” The CDAMM goes on to say, “more recently the terms have been used to refer to secular formulas of salvation, from political visions of social transformation to UFO movements anticipating globally transformative extraterrestrial intervention.”

New Religious Movement (NRM): An umbrella term for religious groups that originated “recently” — from the late 19th-century to today — and are peripheral to its society’s dominant religious culture(s). NRMs can be novel in origin or they can be part of a wider religious tradition, in which case they distinguish themselves from pre-existing denominations. NRMs are also referred to as alternative or emerging religious movements The term is preferred to less neutral descriptors such as “cults” or “sects.” Because the term is so broad, it can include many different groups of many different beliefs. But not all groups that fit the definition of NRM prefer the terminology. Generally it is best practice to ask a representative of the group how to best categorize it, and then to include any additional information or context in your story.

Orthodox/orthodoxy: This term can be used to mean many different things in different contexts. It can refer to a specific church such as the Eastern Orthodox Church, to a branch of observant Judaism or to a style of belief or practice that is considered strict in its interpretation of practice. When used in a broad context, the word is often not capitalized, whereas Orthodox with a capital O tends to refer to a specific set of adherents. It is best to confirm that someone identifies as orthodox before using this term, and to include specifics about their beliefs, practices and rituals to contextualize its use.

Sect: Refers to a group that is an offshoot of another (often bigger) religion or community with its own distinctive religious, political or philosophical beliefs and practices. While the term is commonly used, some groups prefer to think of themselves as “branches” of a religion rather than separate sects.

Shunning: The concept of rejecting someone who has left or been asked/told to leave a community, usually through avoidance and refusal to communicate with that person. Though practices like this do exist in some spaces, it is best to describe the specifics rather than rely on a broad term like “shunning,” which can mean different things and connotes extremism.

Ultra-Orthodox: Used primarily to describe Orthodox Jews (including but not limited to Haredi Judaism, of which Hasidism is a subset) who are particularly observant and adhere to a strict read of Jewish law (also sometimes referred to as Haredi). The term is sometimes considered pejorative, and many prefer not to be referred to as such. It is important to note that there are many different groups that could be categorized in this way. Best practice would be to ask your source how they identify.

Example Coverage

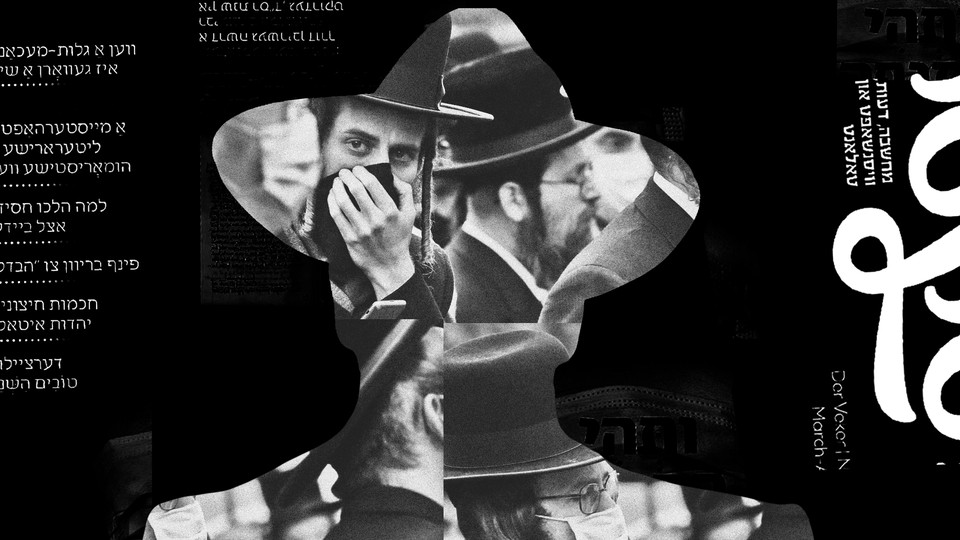

Hasidic, Devout, and Mad as Hell About COVID-19

By Emma Green, The Atlantic

April 9, 2021

(The Atlantic) – A few weeks ago, reuven went to a party. It was indoors. No one wore masks. No one who attended was in any rush to get a vaccine. Reuven and his wife were uncomfortable. But if they hadn’t gone, his relatives would have felt as if he were “judging them” for gathering, “and they judge me back,” he told me. “I have to weigh my options.” Reuven’s parents and siblings roll their eyes when he constantly talks about their risk of getting sick, just as he did at the beginning of the pandemic. He’s meshige far corona, they say. Crazy about the virus.

The Yiddish-speaking, Hasidic Jewish world that Reuven inhabits is intensely communal. Men crowd into synagogues in his Brooklyn neighborhood to pray together three times a day—morning, afternoon, and night. Many large families share small apartments or rowhouses, where they stage elaborate meals each week on Shabbat and during the Jewish calendar’s many holidays, filling their homes with scrambling kids and occasionally the cousins and uncles who live just blocks away. Orthodox Jews in New York are distinctly vulnerable to the virus for many of the same reasons low-income Black and Latino neighborhoods have been hit hard: crowded living spaces, lack of public-health infrastructure, jobs that require in-person work. For many people in these communities, sealing themselves inside their apartments for a year simply wasn’t possible. Reuven knows this; he doesn’t fault the Hasidim for the way they live. “We shouldn’t be judged merely on the fact that we feel that some forms of gatherings are important to us, even during a pandemic,” he told me. “What’s so disappointing and depressing, and even shocking, is the fact that we chose to do all this with zero precautions, for which there is absolutely no excuse.”

New York papers have published plenty of criticism of the Hasidic community’s disregard for COVID-19 safety, covering secretive weddings,massive funerals, and violent anti-lockdown protests. Far less common is pushback like Reuven’s, from within the Hasidic world. This spring, his small, independent Yiddish-language magazine—called Der Veker, meaning “One Who Awakens”—published an investigative report on how the COVID-19 death rates in Hasidic neighborhoods compared with those in other parts of New York State. Based on death notices posted by an establishment Hasidic paper, Der Yid, Reuven and his colleagues concluded that the death rate in their community was three to four times higher than the state average. The number of deaths could have been lower, Der Veker implied, if Hasidic leaders had encouraged their followers to take more precautions—and modeled that behavior themselves. Most Hasidim believe that complaining about the community, especially to outsiders, is like “washing your dirty laundry” in public. “There is no mechanism for self-criticism,” Reuven said. Hasidic Jews who follow particular rabbis are accustomed to heeding their leader’s guidance without question, and those rabbis often crack down on criticism from within their ranks. Reuven worries that speaking out might exacerbate the anti-Semitism the community already faces. But after a brutal year filled with dying, Reuven wants a reckoning—one that will happen, he believes, only under external pressure.

Most Americans would find Reuven’s Brooklyn world foreign. But some people might recognize his dilemma, especially if they live in other communities where the risk of contracting the coronavirus is high and regard for restrictions is low. How could a community that prides itself on generosity and kindness fail to protect its most vulnerable members from a deadly pandemic?

On a recent Friday afternoon before Shabbat, I visited a bakery in the heart of Borough Park’s Hasidic area. Men in black coats circulated busily through the small storefront, collecting pastries and braided loaves of challah to eat that evening, children snaking through their legs. At the time, COVID-19 rates in New York City were roughly as high as they had been during some weeks of the first wave of the pandemic last spring. We all stood in line, shoulder to shoulder, raising our voices to give our orders to three women from outside of the community who stood behind the counter, wearing jeans and black masks. Among the other customers, I didn’t see a single mask.

Example Coverage

Inside the Fringe Japanese Religion That Claims It Can Cure Covid-19

By Sam Kestenbaum, The New York Times

April 16, 2020

(The New York Times) – When New York went into lockdown last month, emissaries of a religious group called Happy Science showed up in a ghostly Times Square to deliver a peculiar end-of-days gospel. They wore ritual golden sashes and huddled in a semicircle.

“Doomsday may seem to be coming,” a young minister said.

“But the greatest savior,” he continued, “our master, is here on earth.”

One or two passers-by lingered, taking in the gloomy scene. Of the few people who were on the street, most rushed past.

None of this was as haphazard as it seemed.

Happy Science is an enormous and powerful enterprise claiming millions of adherents and tens of thousands of missionary outposts across the world. Secretive, hostile to the media, and structured around a tiered, pay-to-progress system of membership, they’re sometimes called Tokyo’s answer to Scientology.

“To many,” The Japan Times wrote in 2009, “the Happies smell suspiciously like a cult.”

The coronavirus pandemic has proved to be a perfect vehicle for the religion’s apocalyptic themes and esoteric doctrines. Its many, many texts are filled with U.F.O.s, lost continents and demonic warfare; now they detail the supernatural and extraterrestrial origins of the virus.

And in addition to the new DVDs, CDs and books for sale, Happy Science is offering “spiritual vaccines” — for a fee, the faithful can be blessed with a ritual prayer to ward off and cure the disease.

In Times Square, the minister wrapped up his speech with a special incantation. He lifted his arms and chopped them to and fro, shouting as he went. His flock cheered and waved homemade placards.

Reporter Tips and Red Flags

To better understand and report on NRMs’ real-life contexts, religion journalist Sarah Ventre embedded herself in Short Creek — a community on the Utah-Arizona border — for three months.

Short Creek was already infamous because of its associations with the FLDS Church when Ventre moved in. Living in the former home of the FLDS Church’s prophet Rulon Jeffs, she detailed the struggles of a town divided not just by state boundaries, but by beliefs. The result was the podcast “Unfinished: Short Creek.”

Preparing for her reporting, Ventre noted the renewed interest in such communities. Although there were dozens of documentaries, podcasts and reality TV shows devoted to the topic, she noted a serious lack of best practices for reporting thoughtfully, carefully and sensitively on religious groups that are new, small or have a vastly different theology than a religion reporter’s core market.

She said, “There is a great need for reporters — and their audiences — to approach these communities and topics with a lot of cultural humility.”

In general, Ventre said, when reporting on these communities, “try replacing the name of the smaller religious community with that of a large one in a sentence and see if it strikes you as odd.

“Would you say that someone escaped the Catholic Church, even if they were abused? Would you say someone was brainwashed by a rabbi? Et cetera,” she said.

Agreeing with Ventre, Shirlee Draper, director of operations for Cherish Families, which provides services and support to families, especially from polygamous cultures, said it’s imperative that newswriters eschew euphemisms, avoid the word “cult” and consider taking an approach to reporting that is trauma-informed.

“Journalists should understand that victims, survivors and former members of these cultures and communities may have experienced serious trauma,” she said, “that means they need to take into consideration how their actions will impact families and individuals once the interview is done and the piece published.”

“In the end, it’s about vulnerability and ameliorating the power differential between survivor and journalist,” said Draper.

Based on her experiences in the field, Ventre shared a list of red flags that reporters and readers should remain aware of when evaluating news stories on NRMs:

- Pieces that make broad generalizations about an entire community.

- Claims about practices and customs without transparent sourcing and fact checking.

- Words that are inherently othering, including: cult, compound, outside world, brainwashing, mind control, etc.

- Pieces that always attribute abusive or problematic behavior to the whole community, rather than those in power or directly responsible, unless there are structural community issues at play.

- Pieces that frame someone’s narrative differently than they frame it themselves.

- Pieces with a lack of critical skepticism toward gatekeepers who claim to speak for a group or have insider knowledge even if they are not a part of that group.

She also shared a big tip:

If you are working on a story about a NRM, it is critical to do your homework ahead of time and think through the best ways to show up for that reporting. Just as you may dress differently or greet someone differently or observe different dietary restrictions in a Catholic church or a Jewish synagogue, the same goes for NRMs. Your best practices are going to be different for different groups, so be sure to find out as much as you can before showing up, and know that you’ll still probably make mistakes. As with all communities, it goes a long way to show that you’re making an effort even if you don’t get it perfectly right.

Example Coverage

Podcast Review: “Unfinished: Short Creek”

By Sarah Larson, The New Yorker

October 5, 2020

(The New Yorker) – Ash Sanders and Sarah Ventre, the hosts of the series “Unfinished: Short Creek,” from Witness Docs and Critical Frequency, spent four and a half years reporting the story of Short Creek, an isolated community of current and former fundamentalist, and polygamist, Mormons on the Utah-Arizona border. With sensitivity, care, and a focus on locals speaking for themselves, Sanders, “a proud Utahan,” and Ventre, “an even prouder Arizonan,” explore how a group originally centered on sharing food, labor, houses, and land became a cult of personality dominated by the church leader Warren Jeffs, who’s now serving a life sentence for sex crimes. John DeLore’s masterly sound design—subtle piano, children singing the credo “Keep Sweet”—helps ground a story of dramatic extremes, as do the voices of women who have left the community. As one says, “God knows where I am, and if she needs me she can find me.”

Example Coverage

Gizmodo Launches ‘The Gateway,’ an Investigative Podcast About a Controversial Internet Spiritual Guru

By Jennings Brown, Gizmodo

May 30, 2018

(Gizmodo) – Teal Swan is an internet spiritual guru who produces hypnotic self-help YouTube videos aimed at people who are struggling with depression and suicidal thoughts. Many of her videos share unorthodox messages about mental health with her hundreds of thousands of fans who follow her on Facebook and Instagram, and in person.

In April 2017, I noticed that Teal Swan’s videos kept popping up in my YouTube recommendations bar. The videos took on a wide variety for topics, from internet addiction to nervous breakdowns to cryptocurrency.

When I finally clicked one, I was both transfixed and unsettled. I started looking into the effect she has on her followers, and why she’s being accused of promoting suicide and running a cult. I went deep within her online devotee communities and traveled to her retreat center in Costa Rica to try to understand this new spiritual movement taking root on the internet. There, I met many of her dedicated volunteers working for her spiritual startup—basically a digital media company creating more content to spread her teachings.

This podcast ended up going places I couldn’t have anticipated. From a decade-old police investigation in Utah to a qigong healing center outside of Beijing, and all the way back to the Satanic Panic of the 1980s.

A Brief Introduction to Several NRMs

While far from comprehensive, the following list of NRMs provides a window into the sheer diversity of movements, communities and traditions included in the capacious category. The list below is meant as a brief introduction to some prominent groups, some that have received a lot of media coverage in the past or that are particularly controversial.

Reporters will take note that the NRMs below emerged out of, or combine, a wide range of religious traditions, including Christianity, Hinduism, Judaism, Islam, New Age, Indigenous Traditions and other moral philosophies. No one religious tradition is more likely to generate an offshoot than any other and many NRMs draw on various streams as they develop their doctrines and practices.

Furthermore, reporters should pay attention to how the terms discussed above are applied to the various movements, which have been the subject of controversy in various contexts.

Ananda Marga: A community with branches in North America and Europe, it was founded in 1955 in Jamalpur, India by Probhat Ranjam Sarkar. A former railway accounts clerk and journalist known by his religious epithet Shrii Shrii Anandamurti, Sarkar founded Ananda Marga on his tantric yoga teachings and the political philosophy “Prout,” which promotes socialist autocracy. Adherents are instructed in the “path of bliss” by a teacher (guru) and are initiated into an ascetic regime of austerity, study and dedicated social service meant to promote personal purity and contentment. The group, however, has proven controversial, with various acts of violence attributed to them and taken against them.

Aum Shinrikyo: Drawing upon interpretations of Buddhist traditions, Hindu traditions, Christian millennialist ideals, yoga and the writings of Nostradamus, its leader Shoko Asahara (originally Chizuo Matsumoto) identifies himself as the “Christ” and “Lamb of God.” Asahara claimed he was to take on the sins of the world and would transfer spiritual power and purity to his followers. The group is best known for carrying out the 1995 Tokyo and 1996 Matsumoto sarin attacks.

Black Hebrew Israelites: Claiming that Black Americans are descendants of the ancient Israelites, Black Hebrew Israelites combine elements from Christian and Jewish traditions, while also exhibiting influences from Freemasonry and New Thought. Not associated with, or accepted by, mainstream Jewish communities, the movement is heterogeneous, with varying beliefs and practices across its various communities (e.g., some believe that Indigenous Americans are also the descendants of Israelites). They have been accused of racism and anti-Semitism.

Branch Davidians: A new religious movement very much connected in the public consciousness with the siege of their headquarters in Waco, Texas in 1993. On 19 April of that year, the siege of the premises by the FBI came to a violent conclusion with the death of 76 people. However, the events at Waco had a complex history, as indeed does the movement known as the Branch Davidians.

The Church of Scientology: An interconnected group of corporate entities and organizations devoted to the practice, administration and dissemination of Scientology, based on the writings of its founder Lafayette Ron (L. Ron) Hubbard and his understanding of the human mind and the path to self-realization and improvement. The Church of Scientology has been the subject of numerous controversies, is frequently labeled a “cult” in popular media, and has been identified by numerous governments as a manipulative for-profit business and not a religion.

Falun Gong: Also known as “Dharma Wheel Practice,” Falun Gong is a moral philosophy founded by Li Hongzhi in China in the 1990s, with a focus on meditation, slow-moving energy exercises and regulated breathing. Strictly anti-communist, the group is perhaps well known for its protests against the Chinese Communist Party, promoting conspiracy theories and far-right political views in its The Epoch Times newspaper and its dance troupe, Shen Yun.

The Family International (also known as TFI and previously named Teens for Christ and The Children of God): A communal missionary movement with broadly Christian influences, TFI was founded in 1968 by David Berg in Huntington Beach, California. Initially interpreted as part of the broader “Jesus People” revival, the group was distinguished by a belief that Berg was God’s “endtime” messenger. Berg has since died and the community now claims some 10,000 members worldwide. TFI has attracted attention for alleged child abuse and for its use of sex in missionary work.

The Fourth Way: Drawing on his gleaning of the teachings and practices of fakirs, monks, and yogis in the “East,” George Gurdjieff developed an approach to self-actualization that combines bodily, emotional, and mental practice. With no specific institutions or regulated forms, this new religious movement is a broad esoteric, occultist, and spiritual movement, based on the belief that human souls are trapped by ordinary personality and consciousness, needing to be woken up by practices such as dances developed by the movement’s founder, known as “Gurdjieff movements.”

Iglesia ni Cristo: An independent and non-Trinitarian Christian community founded in 1913 by Felix Y. Manalo in the Philippines. A restorationist church, Iglesia ni Cristo considers other churches apostate. Manalo is believed by his followers to have been the last messenger of God and while the church remained relatively small in the Philippines at the time of his death in 1963, it has since expanded under his son (Eraño G. Manalo) and grandson (Eduardo V. Manalo) more than 2.5 million members — making it the fourth largest religious community in the country.

The International Society for Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON): Known colloquially as the Hare Krishna movement (or simply “Hare Krishnas”), ISKCON is a Hindu religious tradition (particularly of the Gaudiya Vaishnava variety) founded in 1966 in New York City by A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada. Its core beliefs are particularly drawn from the Hindu texts of the Bhagavad Gita and the Bhagavata Purana. They spread the practice of Bhakti Yoga, which involves dedicating thought and action to Lord Krishna. It is widespread in India, Russia, Eastern Europe, and the United States .

The Nation of Islam (NOI): A Black nationalist religious and political organization founded by Wallace Fard Muhammad in 1930, who drew on various sources, including Noble Drew Ali’s Moorish Science Temple of America, Black nationalist trends such as Garveyism and certain forms of Freemasonry. While it identifies as an Islamic tradition, numerous Muslim groups deny that it is authentically so. The Nation is often characterized as a new religious movement, as it teaches that there has been a succession of mortal gods, each a Black man named Allah (of whom Fard Muhammad is the most recent). It has a deeply detailed cosmogony to promote Black self-sufficiency and separatism. After Fard Muhammad disappearance in 1934, Elijah Muhammad assumed leadership, expanded the NOI’s teachings, and led the organization through the 1950s, 60s, and 70s when it came to prominence through the activities of Malcolm X and boxer Muhammad Ali. Following Elijah Muhammad’s death in 1975, the organization split with his son Warith Deen Mohammed taking the organization in a more Sunni direction, Louis Farrakhan maintaining its more separatist and Black nationalist roots and other groups like the Five Percent Nation developing their own subset of beliefs and practices.

The Nuwaubian Nation: Founded and led by Dwight York (also known as Malachi Z. York), the Nuwaubian Nation originally incorporated elements of Judaism, Christianity, UFO religions, New Age, Islam and esotericism. However, in the late 1980s, York abandoned Black Muslim elements in favor of more UFO and Kemetic (pertaining to ancient Egyptian traditions) orientations. They are particularly well-known for building an Egyptian-themed compound known as “Tama-Re” in Putnam County, Georgia. After York was convicted of child molestation, racketeering and financial charges in 2004, the property was sold. Adherence to the movement has also declined precipitously since York’s conviction. Before that, the Nuwaibian Nation drew thousands of visitors for “Savior’s Day” (York’s birthday, June 26).

Raëlism: A UFO religion founded by Claude Vorilhon (known as Raël) in 1970s France. Raëlism’s cosmogony teaches that an extraterrestrial species known as the Elohim created humanity using their advanced technology. With no formal belief in divine agents, they believe the Elohim have created 40 or so Elohim/human hybrids who have served as prophets (and been mistaken as gods) to prepare humanity for revelations about its origins. Included among them are Buddha, Jesus and Muhammad, with Raël believed to be the 40th and final prophet. Raëlists believe that humanity must find a way to harness new scientific and technological development for peaceful purposes, and that when this has been achieved the Elohim will return to Earth to share their technology with humanity and establish a utopia.

Santa Muerte: With followers across Mexico and in U.S. cities with significant Latino populations (like New York, Houston and Los Angeles) devotees honor the personage of the Grim Reaper: a skeleton — sometimes male, sometimes female — covered in a white, black or red cape, carrying a scythe or a globe. For decades, thousands in some of Mexico’s poorest neighborhoods prayed to Santa Muerte for life-saving or death-defying miracles. While Mexican authorities have linked Santa Muerte’s devotees to prostitution, drugs, kidnappings and homicides, Santa Muerte has developed a large following in the last two decades among Catholics and others disillusioned with the organized and institutional Church and, in particular, the ability of established Catholic saints to deliver them from poverty.

The Triratna Buddhist Community: Previously known as the Friends of the Western Buddhist Order, it was established in 1967 by Dennis Lingwood (Sangharakshita) as a movement devoted to developing Buddhism in a contemporary Western context.

The Unification Church: Sometimes known by the epithet “Moonies,” the Unification Church was founded by Sun Myung Moon in South Korea in 1954 under the name Holy Spirit Association for the Unification of World Christianity. Until his death in 2012, Moon and his wife Hak Ja Han were consider its leaders and honored as their members’ “True Parents.” Their beliefs are based on Moon’s book the Divine Principle, wherein Moon described himself as a second incarnation of Jesus Christ, claiming to complete Jesus’ mission by ushering in a new human lineage and family. The Unification Church is perhaps best known for its mass wedding — or “Blessing” — ceremonies and support for Korean re-unification.

Weixinism (or Weixinjiao): A Chinese salvationist church founded in Taiwan in 1984 by Hun Yuan, it claims a membership of around 300,000. The church has also become popular in mainland China. Weixinism synthesizes Chinese religious traditions and moral philosophies with elements of Christianity. It has been classified as an institutionalization of Chinese traditional religion, rather than a distinct new religious movement.

For further information:

- See the Pluralism Project from Harvard University

- See the World Religions and Spirituality Project (WRSP) at Virginia Commonwealth University

Example Coverage

Despite deaths of its chief promoters, Mexican cult of Santa Muerte prospers

By Jair Cabrera Torres, Religion News Service

July 5, 2019

(Religion News Service) – Since before the Spanish arrived in the 16th century, the image of death has loomed over Mexico, present in festivals, rituals, music, dance and literature. The Mesoamerican cultures that preceded the colonial era had six days a year to celebrate death. A much newer addition is the cult of Santa Muerte, which has become increasingly popular in the past two decades.

Devotion to Santa Muerte has been gaining more devotees every year in Mexico and has expanded to the United States and areas of Central America. A blend of Roman Catholic and indigenous influences, Santa Muerte is a female folk saint that goes by many names, including la Niña Blanca, la Hermana Blanca, la Niña Bonita, la Dama Poderosa, and la Madrina among others. The Catholic Church condemns the movement.

In this small town near Mexico City, the growth of Santa Muerte’s popularity can be traced to a single family that built the world’s largest statue to the folk saint. The Temple of Santa Muerte International was created by the Jonathan Legaria Vargas, known as “the Pantera Commander,” in the early 2000’s.

Example Coverage

Who are the Black Israelites at the center of the viral standoff at the Lincoln Memorial?

By Sam Kestenbaum, The Washington Post

January 22, 2019

(The Washington Post) – In the initial media churn, they were nearly missed.

But a small band of Hebrew Israelites, members of a historic but little-known American religious movement, may actually be at the center of a roiling controversy that has gripped the nation in recent days.

It began with a now-viral video clip, filmed Friday at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, in which high school students from a Catholic school in Kentucky appeared to be in a faceoff with a Native American elder, who was beating on a drum. The boys, some wearing red hats with President Trump’s 2016 campaign slogan, appeared in the clip to be mocking a man, named Nathan Phillips. The clip was widely understood as being centrally about the dangers of Trumpism, and the teens were condemned.

But a longer video soon bubbled to the surface, widening the lens. It showed how a group of half a dozen Hebrew Israelites had, in fact, been goading and preaching at both the Native Americans and high schoolers, using profanity and highly provocative language, for nearly an hour. Phillips later told journalists that he was seeking to defuse tensions between the Israelite group and the high school students by stepping in between them.

Example Coverage

Selling Scientology at the Super Bowl

By Ken Chitwood, Sightings

February 20, 2014

(Sightings) – Suddenly, there it was. Like a spaceship, it appeared and, in a flash, it was gone. It promised a fusion of science and religion, “technology and spirituality combining,” and “that everything you ever imagined is possible.” This was no UFO, but a TV commercial advertising “spiritual technology”—a marketing ploy selling Scientology.

For the second year in a row, The Church of Scientology, a prosperous new religious movement established in the 20th Century by science fiction writer L. Ron Hubbard, invested in a “Super Bowl” ad. Though its 30-second ad did not air during one of the coveted multi-million dollar commercial spots, it broadcast right before halftime in several major local TV advertising markets.

The Church of Scientology likely returned to the lineup of “Super Bowl” ads this year because these ads work. Flying out to California just days later I was perusing the periodicals at an airport newsstand when I noticed a man purchasing Going Clear: Scientology, Hollywood and the Prison of Belief by Lawrence Wright. As he checked out, he said, “that Super Bowl ad got me interested. You know anything about Scientology?”

The Super Bowl is not the first time that Scientology has flirted with pop culture to attract new adherents. It has always been a flashy faith with savvy cultural appeal. Following the example of founder Hubbard, who was adept at reading the times and selling fanciful stories, Scientology’s television marketing is faithful to its heritage.

Its success with religious marketing began with the publication of Hubbard’s sensational, best-selling Dianetics: The Modern Science of Mental Health, which sketched out, along with several of Hubbard’s sci-fi novels, the basics of Scientology. Scientology’s greatest growth occurred during the “golden age” of its TV spots, in the 1980s and 1990s, when its leaders were “masters of book marketing” (except for its PR disaster with Richard Behar’s TIME article and current leader, David Miscavige’s, failed interview on ABC’s “Nightline”).

Part of Hubbard’s grand marketing scheme was to attract Hollywood A-listers, not unlike Tom Cruise or John Travolta, and to cultivate them as glamorous icons of Scientology. He deployed movie-star power at a time when American culture was “bending increasingly toward the worship of celebrity,” wrote scholar Lawrence Wright. Indeed, since The Church of Scientology was incorporated as a religious body in California sixty years ago (February 18, 1954), the movement has always had a bit of “star power” and has been able to grab mass attention with careful cultural cues.

The Super Bowl ad is no different. As one commentator put it, Miscavige, “understands what inspires devotion in people these days…the next great gadget, spiritual contentment…” Playing on our desire to be on the cutting edge of tech and to be “spiritual, but not religious,” Scientology offers both: spiritual technology.

Additionally, Scientology’s second “Super Bowl” ad is an example of a small religion punching above its weight and evoking both curiosity and creepiness. As Wright wrote, “Scientology plays an outsize role in the cast of new religions that have arisen in the twentieth century and survived into the twenty-first.” Though the Church reports millions of members, there are probably just 30,000 Scientologists worldwide, 5,000 of whom are concentrated in Los Angeles. There are twice as many Rastafarians in the world as there are Scientologists.

Like a minor league player batting in the majors, Scientology also uses its more than $1 billion dollars assets to market itself via its Bridge Publications Inc. and International Dissemination and Distribution center in Los Angeles. Due to its shrewd sales approach and to its nearly automatic “cringe factor,” Scientology inspires an oversized amount of fascination.

Of course, religious marketing isn’t solely the property of The Church of Scientology. Noting the success of America’s Protestant mega-churches, many religious organizations have realized the importance of advertising their sacred wares in the U.S.’s spiritual economy. According to Peter Berger, the commercials from your local psychic, the billboards of atheists and bumper stickers from the mega-church down the road are all symptoms of pluralism and public indicators of the ways that various faiths are competing with each other in the religious marketplace.

Given the situation described above, we should expect continued, and comparable, marketing from Scientology. With its financial resources, penchant for the culturalzeitgeist, immense influence, impeccable organization and Hollywood flair we should not be surprised with another ad in next year’s Super Bowl. The only difference next year? I’m hoping that my team, the San Francisco 49ers, will have a comfortable lead going into halftime before Scientology sells itself to the crowds of fans sitting at home in select local markets.

Sources and Experts

Because NRM is an umbrella term, it encompasses many different faiths, traditions, ideologies, and ways of being and believing. The sources and experts below represent, or can provide insight into, a wide range of traditions.

-

Eileen Barker

Eileen Barker is a professor emeritus in the sociology department at the University of London. She studies minority religions, including cults, sects and New Religious Movements, and relevant social conditions.

-

Michal R. Belknap

Michal R. Belknap is an emeritus professor of law at California Western School of Law in San Diego. He wrote the essay “Cults and the Law” for the book Religion and American Law: An Encyclopedia.

-

Henrik Bogdan

Henrik Bogdan is professor in religious studies at the University of Gothenburg, Sweden. His main areas of research are alternative forms of religion, such as Western esotericism, New Religious Movements and secret/initiatory societies.

-

Martha Sonntag Bradley

Martha Sonntag Bradley is a professor of architecture and dean of the undergraduate studies at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City. She is the author of Pedestals & Podiums: Utah Women, Religious Authority & Equal Rights and Kidnapped From That Land: The Government Raids on the Short Creek Polygamists.

-

David G. Bromley

David G. Bromley is a professor of sociology at Virginia Commonwealth University and the University of Virginia, Charlottesville. He specializes in sociology of religion, with a particular emphasis on the study of New Religious Movements and the anti-cult movement. He is co-editor of Cults, Religion, and Violence.

-

Cherish Families

Cherish Families is a nonprofit founded and largely staffed by people from polygamist backgrounds. According to the organization’s website, Cherish Families aims to “connect individuals and families, primarily those from polygamist cultures, with tools and resources for generational success.” Alina Darger is executive director and Shirlee Draper is director of operations.

-

R. Andrew Chesnut

R. Andrew Chesnut is a professor of religious studies at Virginia Commonwealth University. He has written about the growing presence of Pentecostalism in Latin America and the growing popularity of Santa Muerte spirituality.

-

George D. Chryssides

George D. Chryssides is a visiting research fellow in theology and religious studies, York St. John University, U.K. His research has focused on New Religious Movements, including the Jehovah’s Witnesses. He was formerly head of religious studies at the University of Wolverhampton.

-

Communal Studies Association

The Communal Studies Association is a research member association focused on the U.S.’s historical communal sites, intentional communities and communal societies. They publish a journal, host an annual conference and present awards to researchers and other writers in the area of communal studies.

-

Carole M. Cusack

Carole M. Cusack is professor of religious studies at the University of Sydney, Australia. Trained as a medievalist, Cusack has taught about contemporary religious trends, publishing on pilgrimage and tourism, modern pagan religions, new religious movements, the interface between religion and politics, and religion and popular culture since the 1990s.

-

William Ellis

William Ellis is professor emeritus of English and American studies at Pennsylvania State University, Hazleton. He is the author of Aliens, Ghosts and Cults: Legends We Live.

-

Megan Goodwin

Megan Goodwin is a visiting lecturer on philosophy and religion at Northeastern University in Boston and the program director for Sacred Writes, an initiative aimed at increasing public scholarship on religion. She studies and writes about New Religious Movements, minority religions in the U.S., gender, sexuality and race.

-

Edd Graham-Hyde

Edward Graham-Hyde is a researcher and teacher of religion, whose focus includes the terminology around “cults” and “New Religious Movements” as well as specific groups such as the Church of Scientology and the Jehovah’s Witnesses.

-

Stephen Gregg

Stephen Gregg is is senior lecturer in religious studies at the University of Wolverhampton and the honorable secretary of the British Association for the Study of Religions. His background is in 19th-century Hindu philosophy, but in recent years he has specialized in minority religious movements. Contact via the University of Wolverhampton’s experts portal.

-

Steven Hassan

Steven Hassan has written several books about cult experiences, including Freedom of Mind: Helping Loved Ones Leave Controlling People, Cults and Beliefs. Hassan lives in the Boston area.

-

Dusty Hoesly

Dusty Hoesly is a postdoctoral researcher at the University of California, Santa Barbara. He studies New Religious Movements, secularism and how minority faith groups shape American culture.

-

International Cultic Studies Association

The International Cultic Studies Association applies research and professional perspectives on cultic groups to educate the public and help those who have been harmed through the manipulation and abuse of some cultic groups.

-

Joseph Laycock

Joseph Laycock is an assistant professor of religious studies at Texas State University, where he researches New Religious Movements and American religious history.

-

John R. Llewellyn

John R. Llewellyn is a retired Salt Lake County, Utah, sheriff’s lieutenant who extensively investigated polygamy cults. A former polygamist, he wrote Polygamy Under Attack: From Tom Green to Brian David Mitchell; A Teenager’s Tears: When Parents Convert To Polygamy; and Murder of a Prophet: The Dark Side of Utah Polygamy. Llewellyn is now a monogamist and muckraker, and he was lead investigator in two major lawsuits against polygamist cults.

-

J. Gordon Melton

J. Gordon Melton is a distinguished professor of American religious history at Baylor University in Waco, Texas. Formerly, he directed the Institute for the Study of American Religion at the University of California, Santa Barbara. He has written about New Religious Movements and about Christian Science and is an expert on American-born religions. He co-wrote Perspectives on the New Age and has written on New Thought Movements.

-

Timothy Miller

Timothy Miller is a historian of American religion in the religious studies department at the University of Kansas. His expertise is in new and alternative religions, and he has written about the impact of the influx of Eastern spirituality after the 1965 immigration reform act.

-

Amanda Montell

Amanda Montell is a a writer, linguist, and podcast host living in Los Angeles. She is the author of the book Cultish: The Language of Fanaticism and co-host of the Spotify Top 20 podcast, “Sounds like a cult.”

-

Sean O’Callaghan

Sean O’Callaghan is an associate professor of religion at Salve Regina University in Newport, Rhode Island. He studies New Religious Movements, religiously motivated violence and transhumanism.

-

Susan Palmer

Susan Palmer studies New Religious Movements and teaches religious studies at Concordia University and McGill University.

-

Lindsay Hansen Park

Lindsay Hansen Park is host of the “Year of Polygamy” podcast and executive director of the Sunstone Education Foundation, which is a platform to discuss the diverse range of Mormon belief and practice through scholarship, art, short fiction and poetry.

-

Erin Prophet

Erin Prophet is a lecturer in the religion department at the University of Florida. She studies cults and New Religious Movements.

-

Sarah Riccardi-Swartz

Sarah Riccardi-Swartz is an assistant professor of religion and anthropology at Northeastern University, where she is also an affiliate faculty member in the women’s, gender, and sexuality studies program. Before joining Northeastern University she was a Postdoctoral Fellow in the Recovering Truth: Religion, Journalism, and Democracy in a Post-Truth Era project at the Center for the Study of Religion and Conflict (Arizona State University).

-

James T. Richardson

James T. Richardson is Emeritus Foundation Professor of Sociology and Judicial Studies at the University of Nevada, Reno. He wrote the essay “Public Policy Toward Minority Religions in the United States: A Model for Europe?” for the book Religion and Public Policy.

-

Andrew Singleton

Andrew Singleton is a sociologist of religion at Deakin University in Australia. He studies spirituality, New Religious Movements and young people’s relationship with faith.

-

Judith Weisenfeld

Judith Weisenfeld is a professor of religion at Princeton University, where she specializes in American religion, with an emphasis on the 20th century and African American religion. She is the author of Hollywood Be Thy Name: African American Religion in American Film, 1929-1949. She has taught 17 courses, including ones on religion and American film, religion and the civil rights movement, and “cult” controversies in America

-

Catherine Wessinger

Catherine Wessinger, professor of religious studies at Loyola University in New Orleans, has written widely on theosophy, millennialism, New Religious Movements and New Age religions. She is co-editor of Nova Religio: The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions.

-

Benjamin Zeller

Benjamin Zeller is chair of the religion department at Lake Forest College. He focuses on religious currents that are new or alternative, including new religions, the religious engagement with science, and the quasi-religious relationship people have with food.

Related ReligionLink Content

- 50 experts on emerging religious communities

- Ghosts, the paranormal and pop culture

- Beyond ‘The Secret’: self-help, New Thought and more

- Reporting on the U.S. Religious Landscape Survey

Contributors

Sarah Ventre and ReligionLink Editor, Ken Chitwood.

This Reporting Guide was developed with funding from the Henry Luce Foundation via the Luce-American Academy of Religion Advancing Public Scholarship Grant program.