Buckle up, religion reporters, presidential primary season is about to really get underway. With Iowa Republicans gathering to caucus on Jan. 15, New Hampshire’s controversial primaries coming for both parties on Jan. 23 and a flurry of primaries and caucuses following in quick succession after that, U.S. presidential politics are going to take an increasingly prime spot in our news coverage.

The road to 270 Electoral College votes next year will likely careen back-and-forth on a range of issues, from Social Security and Medicare to abortion and immigration. Along the way, it is important not to lose sight of the critical role the faith factor will play in how voters view each issue, potentially deciding who voters will choose in 2024.

As many (re)learned in the last two elections, we ignore religion’s role in presidential elections at our peril.

With next year unlikely to prove an exception to the rule of religion’s influence in presidential politics, this source guide provides an overview of several candidates’ faith backgrounds and angles on how religion may influence their electability in the year to come.

Background

Despite a decline in overall religious adherence, faith continues to influence U.S. politics, not least because, in the shift from privilege to plurality, religious Americans — particularly of the evangelical variety — are not going quietly. The result is that the demographic change, where an increasing number of Americans identify as nonreligious and Christians might soon be a minority, has not meant more consensus, but increasingly polarized debates about the role of faith in U.S. public life.

The fault lines are many and include debates over access to, or restrictions on, abortion, and culture war and church-state separation issues such as banning materials dealing with sexuality and gender identity from schools or discussions of “critical race theory” from the classroom. Feeling ever more like a minority, conservative religious actors have embraced the mantle of “religious freedom,” positioning themselves as needing protection from the encroachments of a leftist agenda, led by a secular majority. All of this is cast against a background of increased “Christian nationalism,” the desire that the nation’s civic life be defined by Christianity — in its identification, history, symbols, values and public policies — and that the government take active steps to enforce this view and impose it on the populace.

At the same time, actors on the religious left can be seen at the front of protests and marches advocating for civil rights, gun control, access to abortion and immigration reform. And prominent Democrats such as Raphael Warnock and Joe Biden position their faith as a core component of their political platforms. The religious left, thought to be dormant for decades, has been quietly resurgent in recent years and may shape the 2024 elections in a significant way.

The impact of these demographic realities, debates and differing perspectives has been uneven, varying from state to state based on their respective populations, politics and histories. Some are asserting a kind of Christian identity and enacting policies that are in line with their interpretation thereof. Others are adopting what they see as more secular laws appropriate for a more plural society.

In any event, religion will — as it always has — play a prominent role in the primary season and, inevitably, during next autumn’s general elections. In fact, this year might feature one of the most religiously diverse batch of presidential candidates we have yet seen, reflecting the nation’s shifting, and increasingly plural, religious landscape.

Republican candidates

Donald J. Trump

Christians of varying stripes supported Donald Trump in his first and second election bids — the first successful, the second not. They were also a strong contingent in the Jan. 6, 2021, insurrection attempt, which sought to overturn the results of the 2020 elections and retain Trump as president. A survey from the Pew Research Center found that 59% of voters who frequently attend religious services backed Trump over Joe Biden in the 2020 election. It is expected that a broad coalition of Christians, including evangelicals and Catholics, will once again rally around Trump as he makes his third bid for the Oval Office. With “diverse attitudes, motivations, and behaviors,” it is difficult to summarize Trump’s Christian-voter base, but he consistently appeals to a wide swath of the 63% of Americans who identify as Christian with his anti-abortion politics and promises to defend Christianity from the “godless left.”

Christians of varying stripes supported Donald Trump in his first and second election bids — the first successful, the second not. They were also a strong contingent in the Jan. 6, 2021, insurrection attempt, which sought to overturn the results of the 2020 elections and retain Trump as president. A survey from the Pew Research Center found that 59% of voters who frequently attend religious services backed Trump over Joe Biden in the 2020 election. It is expected that a broad coalition of Christians, including evangelicals and Catholics, will once again rally around Trump as he makes his third bid for the Oval Office. With “diverse attitudes, motivations, and behaviors,” it is difficult to summarize Trump’s Christian-voter base, but he consistently appeals to a wide swath of the 63% of Americans who identify as Christian with his anti-abortion politics and promises to defend Christianity from the “godless left.”

At the Faith & Freedom Coalition’s policy conference in June 2023, the former president trumpeted that his enemies “are waging war on faith and freedom, on science and religion, on history and tradition, on law and democracy, on God Almighty himself.” He positioned himself, once again, as the presidential candidate most likely to fight back. “No president has ever fought for Christians as hard as I have,” he said.

Raised Presbyterian, Trump now identifies as a nondenominational Christian, joining 13% of U.S. churchgoers and the ranks of previous presidents such as Barack Obama, Rutherford B. Hayes and Andrew Johnson, who were also nondenominational. There have been questions about Trump’s faith, however. With Trump facing multiple criminal indictments and credible accusations of sexual assault, some faith leaders and conservative religious leaders have called for Christians to withdraw their support for a man they view as immoral and unworthy of unabashed support from churchgoers. And, despite attestations of his faith by pastors and spiritual advisers in his orbit, including Paula White and Robert Jeffress, data from Pew Research Center suggests over half of American adults are unsure of Trump’s faith or are convinced he has none at all.

Nevertheless, Trump garnered strong support from white evangelical Protestants in the last election and seems set to do the same in 2024. He is polling well ahead of other Republican candidates and his support for policies evangelicals emphasize (e.g., the overturning of Roe v. Wade and expansion of anti-abortion policies) plays a major part in that groundswell of support.

Ron DeSantis

A Catholic, Ron DeSantis has been uncharacteristically mum about his faith on the campaign trail. A possible reason why? Trying to wrestle away some of the evangelical support that Trump enjoys — a historically hard thing for a Catholic to do. DeSantis held his first rally in Iowa at an evangelical church and ramped up his efforts to court religious conservatives, announcing endorsements in September from pastors and unveiling a “Faith and Family Coalition” made up of more than 70 faith leaders in Iowa, New Hampshire and South Carolina — key nominating states.

A Catholic, Ron DeSantis has been uncharacteristically mum about his faith on the campaign trail. A possible reason why? Trying to wrestle away some of the evangelical support that Trump enjoys — a historically hard thing for a Catholic to do. DeSantis held his first rally in Iowa at an evangelical church and ramped up his efforts to court religious conservatives, announcing endorsements in September from pastors and unveiling a “Faith and Family Coalition” made up of more than 70 faith leaders in Iowa, New Hampshire and South Carolina — key nominating states.

Being quiet about his own faith has not meant he has avoided the topic in general, however. From the beginning, DeSantis has cast his campaign in the language of “spiritual warfare,” calling himself God’s “fighter” and positioning his policies as best placed to “restore religious freedom” in the U.S. Such rhetoric, reporter Tiffany Stanley wrote for The Associated Press, is at the center of his outreach to white evangelicals, as are his hard-charging policies, ranging from Florida’s six-week abortion ban to a spate of laws targeting LGBTQ+ rights, gender-affirming care and the discourse around critical race theory. Whether his staunch commitment to the culture wars will help him surprise Trump in the early primary states remains an open question. Despite a promising start and initial fundraising influx, his poll numbers have him trailing Trump by an average of 40 points.

Nikki Haley

Have you ever changed your Facebook relationship status to “it’s complicated”? If so, welcome to Nikki Haley’s world. The former South Carolina governor and ambassador to the United Nations is the daughter of Indian immigrants, raised in a Sikh household. But in 1997, Haley converted to Christianity and she regularly attends Mt. Horeb church in Lexington, South Carolina, which disaffiliated from the United Methodist Church in 2023. Before leaving, Mt. Horeb was the state’s largest UMC congregation, with 5,000-plus members. She also attends Sikh services once or twice a year and visited the Golden Temple, Sikhi’s preeminent spiritual site, in Amritsar, India, in 2014.

Have you ever changed your Facebook relationship status to “it’s complicated”? If so, welcome to Nikki Haley’s world. The former South Carolina governor and ambassador to the United Nations is the daughter of Indian immigrants, raised in a Sikh household. But in 1997, Haley converted to Christianity and she regularly attends Mt. Horeb church in Lexington, South Carolina, which disaffiliated from the United Methodist Church in 2023. Before leaving, Mt. Horeb was the state’s largest UMC congregation, with 5,000-plus members. She also attends Sikh services once or twice a year and visited the Golden Temple, Sikhi’s preeminent spiritual site, in Amritsar, India, in 2014.

On the campaign trail, Haley not only has to prove her policies and posture, wrote Deseret News’ Natalia Galicza, but also her faith. Rather than being held up as an example of America’s increasingly mixed religious heritage, Haley has been interrogated about her faith repeatedly and various pundits have openly questioned the veracity of her spiritual commitments.

When it comes to policy, Haley hits all the conservative religious talking points, including being loud in her opposition to LGBTQ+ issues. She is also a staunch supporter of Israel. Both policy points were signaled when she had John Hagee, the controversial pastor of Cornerstone Church in San Antonio, Texas, pray at her campaign launch.

At the same time, some commentators have wondered whether Haley’s Sikh background and continued connection to the community might influence how she views foreign policy issues related to the Punjab region of northern India or legal debates about religious liberty in the U.S.

Vivek Ramaswamy

It is hard to get more blunt than the voter who asked Vivek Ramaswamy at a campaign stop in Nevada what his opinion of Jesus Christ is, according to NBC News. The man who asked was not impressed by the answer given by Ramaswamy, who explained his Hindu faith and said that while he acknowledged Jesus as “a son of God,” he did not believe he is “the” son of God.

It is hard to get more blunt than the voter who asked Vivek Ramaswamy at a campaign stop in Nevada what his opinion of Jesus Christ is, according to NBC News. The man who asked was not impressed by the answer given by Ramaswamy, who explained his Hindu faith and said that while he acknowledged Jesus as “a son of God,” he did not believe he is “the” son of God.

If Haley is facing questions about the veracity of her conversion, Ramaswamy has been consistently quizzed by caucusgoers in Iowa for his lack thereof. Ramaswamy has swung back and forth between underlining his pride in being Hindu and segueing into promises of defending religious liberty and quoting Bible verses in his stump speeches.

But the fact that he is not a Christian may outshine his surprising, some say cringeworthy, performances in a string of Republican debates — all not including Trump, who has refused to participate — especially in places like Iowa. There, almost 2 of every 3 Republicans in the 2016 Iowa caucuses identified as evangelical or born-again Christian, according to NBC News’ exit poll.

In part to assuage evangelical voters’ apprehensions about his Hindu faith, Ramaswamy has been quoted saying that while he is not Christian, he believes the U.S. is “a nation founded on Judeo-Christian values” and that he shares those values. And, among his “10 Truths” that Ramaswamy says form the backbone of his campaign, the first is: “God is real.”

Time will tell if Ramaswamy’s appeals to evangelicals through a consistent message of “faith, family, hard work and patriotism” can court the religious voters he almost certainly needs to spring a surprise in Iowa and the early primary states.

Chris Christie

Chris Christie is a Catholic. That, in itself, is already notable, as Catholics have historically been a minority in the Republican Party. But in this round of primaries, not one but two candidates profess a Catholic faith (the other being DeSantis, profiled above).

Chris Christie is a Catholic. That, in itself, is already notable, as Catholics have historically been a minority in the Republican Party. But in this round of primaries, not one but two candidates profess a Catholic faith (the other being DeSantis, profiled above).

With that said, Christie’s Catholicism will not necessarily hold him back. While the only two presidents to have been Catholic were Democrats (John F. Kennedy and Joe Biden), Catholics have been playing an increasing role in the Republican Party’s faith-based voting pool. During the 2016 campaign, there were even six Catholics among the 17-strong field. Rick Santorum, one of those Catholics, was even deemed “an evangelical at heart” among Iowans who supported him.

Christie, who was raised Catholic, married Catholic, sent his kids to Catholic schools and counted former Newark Archbishop John J. Myers as a “dear friend,” will probably not be named an honorary evangelical any time soon. With that said, the cradle Catholic’s positions generally fall in line with the tenor of white evangelical politics: He opposes abortion (but acknowledges having used birth control) and same-sex marriage (though he does not believe homosexual acts are a sin and opposes so-called gay conversion therapy), and he advocates for greater religious freedom for conservative religious individuals and their businesses. In a Republican primary debate in November, Christie advocated what has often been seen as a more Catholic line on the “pro-life” cause, saying: “The bigger issue is we’re not pro-life for the whole life. To be pro-life for the whole life means that the life of a 16-year-old drug addict on the floor of a county lockup is precious and we should get treatment for her.”

Nonetheless, his greatest sin may be that he strongly opposes Trump. At the the Faith & Freedom Coalition’s annual conference in June, he was booed as he came out swinging against the former president. This, rather than his Catholic faith, may prevent him from reaching the voters he needs to gain a foothold in this primary race.

Democratic candidates

Joseph R. Biden

President Joe Biden’s Catholic faith is no secret. On the campaign trail in 2020, he made a big deal of it, with an emphasis on healing, wisdom (riffing on Ecclesiastes, a book in the Hebrew Scriptures, referred to as the Old Testament by most Christians) and quoting one of his favorite Catholic hymns (“On Eagles’ Wings”) during his victory speech. On Inauguration Day, he attended Mass at Washington’s Cathedral of St. Matthew the Apostle.

President Joe Biden’s Catholic faith is no secret. On the campaign trail in 2020, he made a big deal of it, with an emphasis on healing, wisdom (riffing on Ecclesiastes, a book in the Hebrew Scriptures, referred to as the Old Testament by most Christians) and quoting one of his favorite Catholic hymns (“On Eagles’ Wings”) during his victory speech. On Inauguration Day, he attended Mass at Washington’s Cathedral of St. Matthew the Apostle.

But Biden has sometimes stumbled on certain core progressive concerns when they conflict the more conservative elements of the Catholic faith. Two issues in particular might prove an uncomfortable conversation for Biden: abortion and LGBTQ issues. While campaigning in Maryland in June 2023, Biden said that although he may not be “big on abortion” because of his Catholic faith, the now-overturned Roe v. Wade decision “got it right.” Praised for some of his positions on key LGBTQ issues, he has been critiqued on other fronts, especially when it comes to the major culture-war debates around Title IX transgender athletes’ participation in school sports.

Whether as rallying point or tense touchpoint, religion reporters should expect Biden’s Catholic identity politics to feature yet again in 2024.

Marianne Williamson

Soon after announcing her candidacy in the 2024 election cycle, Marianne Williamson told attendees at an event at Yale’s Political Union, “If you think politics has nothing to do with religion, you don’t understand religion.” Though this is not news to religion newswriters, Williamson’s own brand of pop spirituality and self-help religion is perhaps a bit different from the sometimes straightforward Judeo-Christian makeup of presidential hopefuls.

Soon after announcing her candidacy in the 2024 election cycle, Marianne Williamson told attendees at an event at Yale’s Political Union, “If you think politics has nothing to do with religion, you don’t understand religion.” Though this is not news to religion newswriters, Williamson’s own brand of pop spirituality and self-help religion is perhaps a bit different from the sometimes straightforward Judeo-Christian makeup of presidential hopefuls.

Writing for The New York Times, Sam Kestenbaum told about how Williamson drew from a renowned 1976 text of “homegrown American” spirituality — Helen Schucman’s A Course in Miracles — in a Democratic primary debate. Such profiles helped highlight that Williamson is not simply a candidate, but a celebrity spiritual guide who has sold millions of books and tapes. Dismissed by some as shallow, others as a self-help guru, she frames her candidacy as being about more than politics, but about saving the U.S. “from spiritual bankruptcy.”

Dean Phillips

Phillips, who only recently entered the 2024 race for the White House, may be a long shot in procuring the presidency, but he’s got quite the backstory. One of 22 Jewish Democrats currently serving in the House — and the first Jewish Minnesotan elected as a U.S. Representatives — Phillips is the heir to his family’s distilling company who invested in a small gelato business, which became one of the top-selling ice cream brands in the country.

Phillips, who only recently entered the 2024 race for the White House, may be a long shot in procuring the presidency, but he’s got quite the backstory. One of 22 Jewish Democrats currently serving in the House — and the first Jewish Minnesotan elected as a U.S. Representatives — Phillips is the heir to his family’s distilling company who invested in a small gelato business, which became one of the top-selling ice cream brands in the country.

With a focus on electoral reform, healthcare costs, global climate change, immigration and gun violence, Phillips is the descendant of Jewish refugees who fled to the U.S. to escape pogroms in eastern Europe.

Phillips has said his Jewish identity is at the core of his politics. And Phillips has shown he’s willing to invoke his faith when necessary. In March, Phillips demanded an apology from fellow Minnesota Democrat Rep. Ilhan Omar after she charged that American supporters of Israel have “allegiance to a foreign country.” A month earlier, responding to another controversial comment by Omar, Phillips said that she had “propagated dangerous and destructive stereotypes of the Jewish people and the State of Israel.”

Cenk K. Uygur

Cenk Uygur is more than a dark-horse Democratic presidential hopeful. Announcing his candidacy in October 2023, Uygur has struggled to get on state ballots (currently, he is only on Arkansas’ ballot) because he is not a natural-born U.S. citizen. Some have taken note how he has proposed some novel legal theories to justify his candidacy, but his perspective and experience with religion might be of particular interest for ReligionLink readers.

Cenk Uygur is more than a dark-horse Democratic presidential hopeful. Announcing his candidacy in October 2023, Uygur has struggled to get on state ballots (currently, he is only on Arkansas’ ballot) because he is not a natural-born U.S. citizen. Some have taken note how he has proposed some novel legal theories to justify his candidacy, but his perspective and experience with religion might be of particular interest for ReligionLink readers.

Uygur was raised in a “not-very-strict” Muslim household, but “lost his faith after taking a college course about Islam” and reading religious texts, according to the Freedom From Religion Foundation. He still identifies as a cultural Muslim, even as he claims the monikers of secular humanist and agnostic. His YouTube commentary show, “The Young Turks,” is named after the Young Turks, a secular nationalist political reform movement in Turkey in the early 20th century. Uygur sparred with Ramaswamy about church-state separation and the Republican presidential candidate’s own takes on religion and secularism soon after announcing his candidacy.

Independent and third-party candidates

Robert F. Kennedy Jr.

The Kennedy name is pretty much synonymous with Catholicism. Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s uncle was the nation’s first Catholic president, and his late father, former U.S. Attorney General Robert “Bobby” Kennedy, was described as the “most-Catholic Kennedy.” But RFK Jr.’s faith journey is a bit more complex.

The Kennedy name is pretty much synonymous with Catholicism. Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s uncle was the nation’s first Catholic president, and his late father, former U.S. Attorney General Robert “Bobby” Kennedy, was described as the “most-Catholic Kennedy.” But RFK Jr.’s faith journey is a bit more complex.

In a well-known interview with scientist and podcaster Lex Fridman, RFK Jr. talked candidly about how after growing up in an observant Catholic family, he fell away from the faith as he became furiously addicted to drugs and alcohol. It was when a fellow addict became a follower of the Rev. Sun Myung Moon and his Family Federation for World Peace and Unification — widely known as the Unification Church — and cleaned up his act that RFK Jr. was inspired to pursue faith as a means of overcoming addiction. “I had a spiritual awakening, and my desire for drugs and alcohol was lifted. Miraculously,” he said.

RFK Jr. identifies as a Roman Catholic and has said he considers St. Francis of Assisi a patron saint and role model, especially when it comes to his views on the environment. Though he previously expressed support for a three-month federal abortion ban, his campaign released a statement walking back his comments on the issue, saying RFK Jr. believes “it is always the woman’s right to choose. He does not support legislation banning abortion.”

RFK Jr. believes the Catholic Church “should be an instrument of justice and kindness around the world.” At the same time, his “anti-establishment vibes,” wrote Bonnie Kristian for Christianity Today, have made him increasingly popular among white evangelicals. Time will tell whether his name, unique brand of politics and spirituality as well as controversial vaccine claims that helped catapult him as a potential candidate, might make him an independent to sway 2024 election results.

Jill Stein

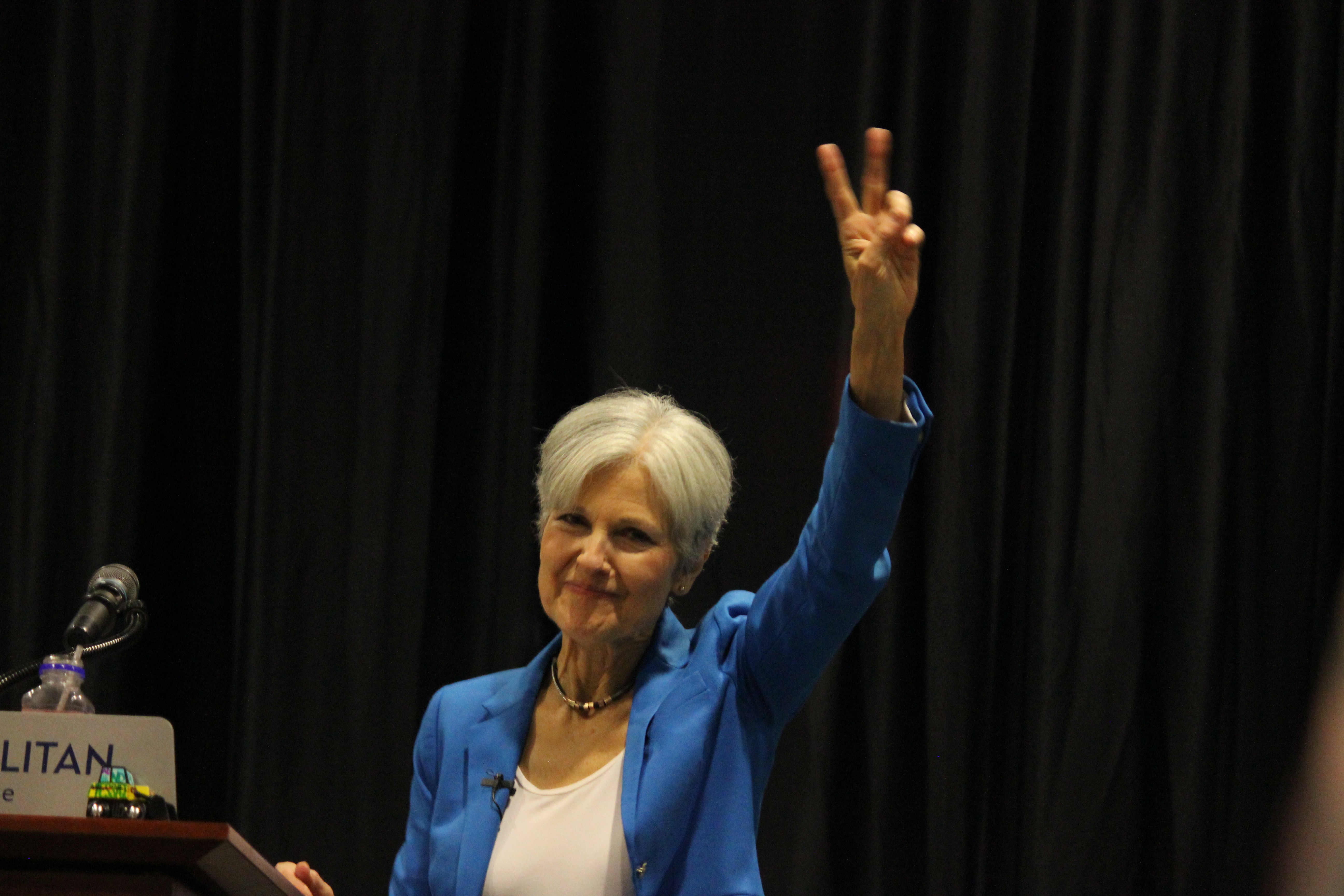

The long-shot Green Party candidate is perhaps best known for being a physician turned outspoken environmental activist — and a potential third-party spoiler, who some Democrats claim cost Hilary Clinton the election in 2016.

The long-shot Green Party candidate is perhaps best known for being a physician turned outspoken environmental activist — and a potential third-party spoiler, who some Democrats claim cost Hilary Clinton the election in 2016.

But religion reporters will take note that Stein, who is descendant from Russian Jews and grew up in a Reform Jewish household in Chicago’s North Shore, has said the Reform tradition’s emphasis on social justice has had a “huge” influence on her political positions. No longer a “practicing Jew,” Stein told Forbes in 2012 that Jewish values continue to shape her, “including the importance of taking social responsibility, the importance of speaking up when you see things going on in your community that aren’t right.”

For Stein, that means advocating for workers’ rights, pushing for urgent environmental reforms and advancing a non-interventionist foreign policy. Controversially, she has accused Israel’s government of “apartheid, assassination, illegal settlements, blockades, building of nuclear bombs, indefinite detention, collective punishment, and defiance of international law” and the current U.S. administration of “war crimes” against the Palestinian people. Such positions have drawn ire from conservative Jewish groups, among others.

Cornel West

As Ethan Bauer of Deseret News put it, “No candidate in the 2024 field boasts more overt religious credentials than Cornel West.” Religious credentials indeed. A highly regarded scholar, West has taught religion at Princeton, Yale and Harvard. He now serves as professor of philosophy and Christian practice at Columbia University’s Union Theological Seminary.

As Ethan Bauer of Deseret News put it, “No candidate in the 2024 field boasts more overt religious credentials than Cornel West.” Religious credentials indeed. A highly regarded scholar, West has taught religion at Princeton, Yale and Harvard. He now serves as professor of philosophy and Christian practice at Columbia University’s Union Theological Seminary.

West’s personal faith perspectives are rooted in the Black Protestant tradition and he has referred to himself as “a revolutionary Christian” and “Christian socialist.” Co-founder of the Network of Spiritual Progressives and “perhaps the leading Christian thinker on the American left,” West emphasizes Jesus’ teachings on love and justice and has been a vociferous critic of white Christian nationalism.

Related stories and commentary

- Read “It’s a bit late for Trump to be derailed over ethical questions,” from The Washington Post on Nov. 28, 2023 (Commentary).

- Read “Trump, MAGA and the insidious underbelly of white supremacy in America,” from The Hill on Nov. 28, 2023.

- Read “In a world where Christ is king, authoritarian leaders can only be antichrists,” from Religion News Service on Nov. 27, 2023 (Commentary).

- Read “Trump, Who Destroyed Roe, Thinks He Can Run As an Abortion ‘Moderate’ in 2024,” from Rolling Stone on Nov. 26, 2023.

- Read “We need to hear from the presidential candidates about poverty,” from Religion News Service on Nov. 24, 2023 (Commentary).

- Read “Trump called Iowa evangelicals ‘so-called Christians’ and ‘pieces of shit’, book says,” from The Guardian on Nov. 23, 2023.

- Read “Vivek Ramaswamy Struggles to Gain Traction With Iowa Republicans as Critics Question His Path Ahead,” from US News and World Report on Nov. 21, 2023.

- Read “DeSantis Picks Up Key Endorsement From Iowa Religious Leader,” from The New York Times on Nov. 21, 2023.

- Read “US Elections 2024: I am a Hindu, it’s my duty to realise God’s purpose, says Vivek Ramaswamy about Presidential bid,” from Mint on Nov. 19, 2023.

- Read “Miscarriages, abortion and Thanksgiving – DeSantis, Haley and Ramaswamy talk family and faith at Iowa roundtable,” from CBS News on Nov. 17, 2023.

- Read “Catholic leaders meet with White House on climate change,” from Religion News Service on Nov. 17, 2023.

- Read “In new political document, Catholic bishops emphasize abortion over climate change,” from Religion News Service on Nov. 15, 2023.

- Read “For historically conservative Jewish Americans, Biden’s response to Israel receives praise,” from NBC News on Nov. 14, 2023.

- Read “Progressive Minnesota US Rep. Ilhan Omar draws prominent primary challenger,” from Religion News Service on Nov. 13, 2023.

- Read “Faith and the candidates,” from Deseret News on Oct. 29, 2023.

- Read “Donald Trump and the Exceptions of American Evangelicalism,” from Sightings from the University of Chicago on Oct. 12, 2023.

- Watch “How GOP presidential candidates are courting evangelical voters in Iowa,” from PBS NewsHour on Sept. 18, 2023.

- Watch “The role religion plays in today’s Republican Party,” from Spectrum News on Sept. 1, 2023.

- Read “Black Muslims will play a big role in the next election. Join us,” from Religion News Service on Aug. 30, 2023.

- Read “Will Trump’s latest indictment hurt him with evangelical Christians? Probably not,” from Religion News Service on Aug. 4, 2023.

- Read “Crowded GOP field vies for the Christian Zionist vote as Israel’s rightward shift spurs protests,” from Religion News Service on July 20, 2023.

- Read “Field of presidential candidates faces crowd of Christians,” from Iowa Capital Dispatch on July 14, 2023.

- Listen to “Republican presidential candidates vie for the influential evangelical Christian vote,” from NPR on July 13, 2023.

- Read “Evangelicals and Catholics dominate list of 2024 presidential candidates,” from Still More to Say on May 7, 2023 (Commentary).

- Read “2024 GOP Presidential Candidates Fight for the Evangelical Vote: ‘This Is a Judeo-Christian Nation’” from the Christian Broadcasting Network on April 5, 2023.

- Read “Can DeSantis break Trump’s hold on the religious right?” from Religion News Service on March 30, 2023 (Commentary).

- Read “Evangelical influencers pan Trump as driven by ‘grievances and self-importance’” from Religion News Service on Nov. 30, 2022.

- Read “How evangelical Christians are sizing up the 2024 GOP race for president,” from Politico on June 18, 2022.

Sources

-

Tim Alberta

Tim Alberta is a staff writer for The Atlantic magazine and formerly served as chief political correspondent for Politico. In 2019, he published American Carnage: On the Front Lines of the Republican Civil War and the Rise of President Trump and co-moderated the year’s final Democratic presidential debate aired by PBS NewsHour. His new book, The Kingdom, The Power, and The Glory: American Evangelicals in an Age of Extremism is a deeply personal examination of the divisions that threaten to destroy the American evangelical movement.

-

Ballotpedia

Ballotpedia maintains a list of key staffers, including press contacts, communications directors and media consultants for various campaign teams.

-

Matthew Brooks

Matthew Brooks is the chief executive officer of the Republican Jewish Coalition, a political organization working to strengthen ties between the Republican Party and American Jews.

-

Jen Butler

The Rev. Jen Butler is the founder and former CEO of Faith in Public Life, a progressive, faith-based organization that advocates for better policies on immigration, LGBTQ rights and other issues. She is ordained in the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) and previously served as chairwoman of the White House Council on Faith and Neighborhood Partnerships.

-

Christians Against Christian Nationalism

Christians Against Christian Nationalism is a large group of faith leaders concerned that Christian nationalism presents a persistent threat to both religious communities and democracy. Amanda Tyler of the Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty is lead organizer. The press contact is Guthrie Graves-Fitzsimmons.

-

John C. Danforth Center on Religion and Politics

The John C. Danforth Center on Religion and Politics advances the study of the intersection of religion and politics and publishes the journal Religion & Politics. It is based at Washington University in St. Louis. Mark Valeri is interim director.

-

Dayenu

Dayenu is a multigenerational Jewish movement that aims to confront the climate crisis with spiritual audacity and bold political action.

-

Joshua A. Douglas

Joshua A. Douglas is a law professor and voting rights expert at the University of Kentucky. He wrote Vote for US: How to Take Back Our Elections and Change the Future of Voting.

-

Faith in Public Life

Faith in Public Life is “a strategy center for the faith community advancing faith in the public square as a powerful force for justice, compassion and the common good.”

-

R. Marie Griffith

R. Marie Griffith is the John C. Danforth Distinguished Professor in the Humanities at Washington University in St. Louis. For 12 years, she served as director of the university’s John C. Danforth Center on Religion and Politics. She has written on women in charismatic and Pentecostal movements.

-

Andrew Hall

Andrew Hall is co-director of the Democracy & Polarization Lab at the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research. He also is a political science professor and his areas of expertise include how to safely administer elections during the pandemic.

-

Vincent Hutchings

Vincent Hutchings is a political science professor at the University of Michigan. He is an expert on public opinion, elections, voting behavior and African American politics.

-

Matthew Kaemingk

Matthew Kaemingk is a Christian ethicist and public theologian engaging questions of Christian involvement in politics, culture and the marketplace. He serves as the Richard John Mouw Associate Professor of Faith and Public Life at Fuller Theological Seminary. He also directs the Mouw Institute of Faith and Public Life.

-

Steven Krueger

Steven Krueger is the president of Catholic Democrats.

-

Prema Kurien

Prema Kurien is a professor of sociology at Syracuse University. Her books include A Place at the Multicultural Table: The Development of an American Hinduism and Ethnic Church Meets Mega Church: Indian American Christianity in Motion.

-

Lerone A. Martin

Lerone A. Martin is director of American culture studies at Washington University in St. Louis and associate professor of religion and politics, with additional research background and publications on African and African American studies.

-

Russell Moore

Russell Moore is editor-in-chief of Christianity Today. Named in 2017 as one of Politico Magazine’s top fifty influence-makers in Washington, Moore was previously President of the Southern Baptist Convention’s Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission.

-

Nancy Sinkoff

Nancy Sinkoff is professor of Jewish studies and history at Rutgers University. Sinkoff’s research interests include Jewish history, Jewish politics, Jewish labor and the Jewish left.

-

Charles Stewart III

Charles Stewart III is a political science professor at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. His areas of expertise include congressional politics, elections and American political development.

-

Matthew D. Taylor

Matthew D. Taylor is a scholar at the Institute for Islamic, Christian and Jewish Studies, where he specializes in Muslim-Christian dialogue, evangelical and Pentecostal movements, religious politics in the U.S. and American Islam. Media inquiries should be directed to ICJS’ communications and marketing director, John Rivera.

-

Karma Lekshe Tsomo

Karma Lekshe Tsomo is an associate professor of religion at the University of San Diego who teaches Buddhist ethics, feminist ethics, bioethics (abortion, euthanasia, organ transplantation) and the ethics of war and peace. She is co-founder of Sakyadhita: The International Association of Buddhist Women and founding director of Jamyang Foundation, an initiative to provide educational opportunities for women in the Indian Himalayas.

-

Ali A. Valenzuela

Ali A. Valenzuela is an associate professor at American University in Washington D.C. His research focuses on race and racism in U.S. politics and campaigns; Latina/o/x attitudes, preferences and turnout in U.S. elections; immigration and demographic change in the U.S. and its political consequences; U.S. public opinion and voter behavior; as well as ethno-racial and religious identities in politics.

-

Jon Ward

Jon Ward is chief national correspondent at Yahoo!News, where he writes about politics, culture and religion. Ward is the author of Camelot’s End: Kennedy vs. Carter and the Fight That Broke the Democratic Party and Testimony: Inside the Evangelical Movement That Failed a Generation. Contact via publicist Kelly Hughes.

-

Ani Zonneveld

Ani Zonneveld is the founder and president of Muslims for Progressive Values, which combats radical Islam, and a board member for the Alliance of Inclusive Muslims, which works to counter gender, racial and sexual bias in the Muslim community worldwide. She is based in Los Angeles.

Related source guides

- Five religion stories to cover postelection

- 23 experts on the religious response to voter access bills

- 20 experts to help explain antifa, Proud Boys and others grabbing headlines during this election season

- 20 experts to help you cover the impact religious voters may have on the presidential election

- Evangelicals’ evolving role in the 2016 election